What is the Optimal Time to Recover from Birth or Pelvic Surgery?

But that doesn’t mean you should be on bedrest, either…

Six weeks is commonly the timeframe many obstetricians advise “pelvic rest” for women after birth, which is the same advice many gynecologists give their patients after pelvic surgery. The typical spiel is that women during that time should avoid anything inside the vagina, including intercourse, tampons, and submersion in water (ex. hot tubs, pools, baths). In that same window, women are often advised to avoid heavy lifting and exercise. After that, women are often given the ok to resume normal life. But at six weeks after my baby, why didn’t I feel ready to jump back into my normal activities?

The “Pelvic Rest”

At six weeks postpartum I overall felt well, new mom-fatigue aside. I had an uncomplicated birth and started doing some basic core work in the first 1–2 weeks after delivery. At four weeks I felt well enough to walk around our local botanical garden. By six weeks I was back to doing squat exercises, so I figured I’d be right on schedule to start safely having sex. Unfortunately, I barely made it past first base — just being in position with my knees open was uncomfortable, and I felt like there was sandpaper on the outside of my vagina.

What I was experiencing was something I knew well because of my medical training. But I didn’t truly understand it until I’d gone through it myself. Women after baby experience many hormonal shifts, including a drop in estrogen. This low estrogen state can continue while women breastfeed, and because of that women can have intense vaginal dryness (hence the sandpaper sensation I was feeling). In addition, it can take up to five months for tissue to recover after an injury, including childbirth or pelvic surgery. In most cases, the pelvic muscles and the ligaments holding the pelvis together are never truly the same.

Physical recovery aside, there is a large psychological component to sex, including interest and arousal. All of that is affected in the postpartum period. In one study of normal women in pregnancy, sexual function did not return to women’s baselines by 6-months postpartum, so going back to normal sex life after baby may take longer than that. Throw in birth complications, stressful home life, and postpartum depression or other mood disorders, and sex after baby may just fall low on the list of priorities. It’s not hard to imagine that many women are secretly wondering what is “normal” when in fact, a return to “normal” is highly variable and probably takes longer than most people expect.

Postpartum and post-pelvic surgery sexual “dysfunction” is common. One review cites 40–80% of women express some concerns with sex between 3–6 months after baby. However, I hesitate to call this a dysfunction if it’s so common — it seems that it’s more like the norm. For women after pelvic surgery, the majority will eventually experience improved quality of their sex lives postoperatively, however, this may not be the case in early recovery. Many of my patients at six weeks still express to me that they just don’t feel ready to start having sex again, whether it’s for concern of injuring their vaginal scars, concerns about pain, or just lack of interest due to fatigue. I always reassure women in this situation that sex may be “safe” if their scars appear healed on exam, however women should only resume sexual activity when they feel ready.

Exercise after Baby or Pelvic Surgery

I cringe to think that one of my mentors, who is an otherwise excellent surgeon and clinician, tells her patients to just stop exercising after pelvic reconstructive surgery. Really? I would wonder. Should they stop exercising for the rest of their lives? For pelvic reconstruction, which is a quality of life surgery, this just seems counter-intuitive. In addition, a sedentary lifestyle is just unhealthy.

The six-week rule for recovery after surgery or after baby comes from our scientific understanding of tissue remodeling. This study cites that up to 80% of tissue repair happens in the first 6 weeks, and it continues for up to 5–6 months afterwards. However, it seems that there is a poor understanding among surgeons and obstetricians regarding life after pelvic surgery or after baby. I would argue that part of that is due to the way we are taught to do research: we’re commonly taught to isolate causative variables to understand effect, when in reality, recovery is a complex process. We can’t just look at intra-abdominal pressure and its effect on the recovering pelvic floor, or just study the properties of wound healing to understand healing in the entire body. We have to look at whole people, living whole lives that involve complex activities.

My physical therapy colleagues are much more familiar with the practical information about exercise after baby or after pelvic surgery. In general, I think doctors can be too restrictive about exercise in the initial period, and then we give the green light at six weeks to resume normal activity without a good understanding of what that means for the patient in front of us.

On one hand, although activity should be modified after baby or after pelvic surgery, that does not equate to being inactive. In fact, it’s only recently that early ambulation has become recognized as an important part of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery, or ERAS. In short, for outpatient procedures (like many pelvic surgeries), people should be encouraged to be out of bed as much as possible and to walk as much as tolerated.

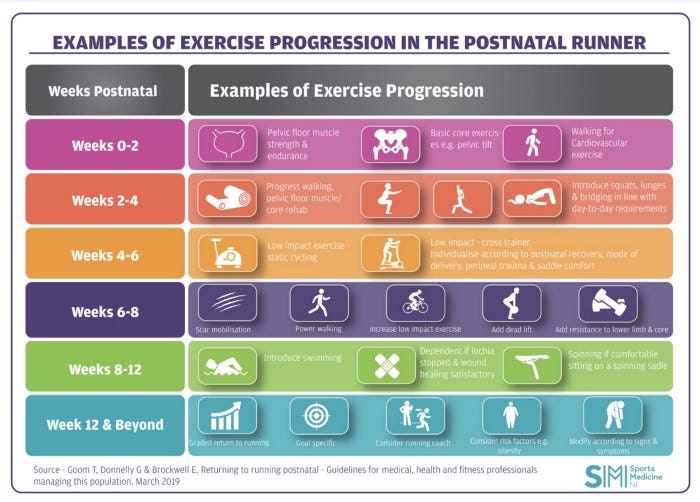

For postpartum patients, there’s a growing appreciation that women should begin exercise immediately postpartum. The exercises should be appropriate and gradually increase in variety and intensity. This is an example of how to increase activity after baby for running.

For women after pelvic reconstructive surgery in particular, there is not a lot of research about how to work toward exercise postoperatively. A lot of physiotherapy sites give details about low impact workouts, but what about women that want to incorporate strength training or occasional high impact activities? What about women who work as caregivers and have to lift heavy clients, or factory-workers who carry heavy boxes, or women in other physically demanding jobs? I think the conventional wisdom has been to avoid that, but it’s just not realistic for many postoperative women and we don’t actually have the data to back up our advice to “just avoid __.”